Legal Spotlight

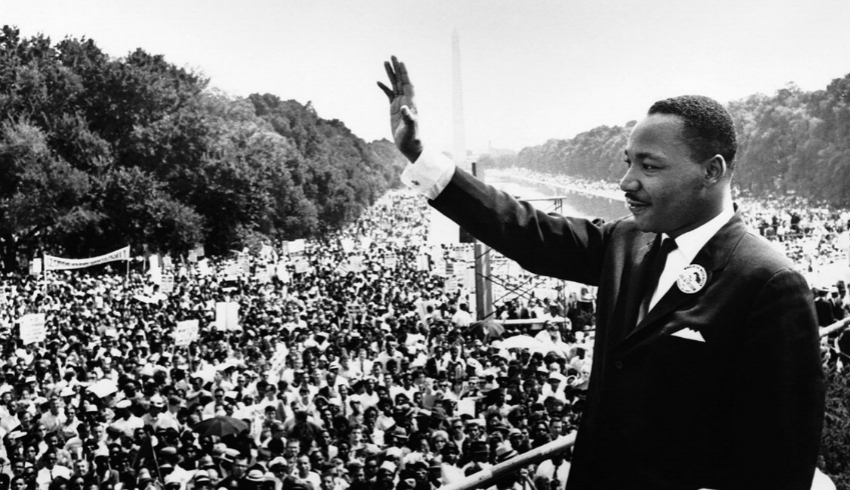

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the assassination of Martin Luther King and Enoch Powell’s ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech: both touchstone moments in the history of Western race relations. So how has legislation in the past half-century bridged gaps and righted wrongs? And what still needs to be done?

On April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King—civil-rights leader and hero to a generation of Americans—was staying in a Memphis hotel. While he was standing on the balcony at 6.01pm, he was shot by a single bullet fired from a Remington Model 760 rifle. King was rushed to hospital, but he never regained consciousness and was pronounced dead at 7.05pm.

Just weeks later in the UK, on April 20, Enoch Powell delivered his so-called ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech to a Conservative Association meeting in Birmingham. The fallout was swift and fierce—on both sides. Protesters took to the streets in support of Powell’s backing for the deportation of immigrants, while condemnation appeared in newspaper editorials attacking his “appeal to racial hatred”. Powell himself was thrown out of the Conservative shadow cabinet, effectively ending his political ambitions.

It was around this time that race relations (and racism) in the UK was beginning to be taken seriously in legislation. On December 8, 1965, the first Race Relations Act came into force, defining “racial discrimination” as treating one person less favourably than another on the grounds of race. The follow-up Race Relations Act of 1976 attempted to be more specific: it made both direct and indirect discrimination an offence, and gave those affected by discrimination redress through employment tribunals and the courts.

In 2001, another amendment to the Act brought public bodies— including local authorities and police—under its scope for the first time, obliging them to ensure their policies resulted in the equal treatment of all.

Almost a decade later, the Equality Act 2010 came into force, which legally protected people from discrimination in the workplace and in wider society. It replaced previous antidiscrimination laws with a single Act, attempting to make the law easier to understand and strengthen protection in some situations. It sets out the different ways in which it’s unlawful to treat someone.

The effect of legislation

Employment-tribunal claims relating to ethnicity can go some way to demonstrate how these equality regulations have been used. Data published by the Department for Business last year show that in 2007, 14% of employment tribunal claims were made by people from Asian, Black, “Mixed” and “Other” ethnic groups, while employees from these groups made up 9% of the total working population.

In 2012, 18% of claims were made by people from the Asian, Black, “Mixed” and “Other” ethnic groups, while employees from these groups made up 10% of the total working population. Where the employment tribunal related to discrimination, around a quarter of claims were made by people from the Asian, Black, “Mixed” and “Other” ethnic groups in both 2007 and 2012. So-called “stop and search” laws are another key part of the race-relations legislative landscape over the last 50 years. These first came to national prominence with the notorious Brixton riots: in 1981 police launched Operation Swamp, in an attempt to deal with south-London street crime.

Officers used so-called “sus” laws to search large numbers of young black men in Brixton. The resentment surrounding the implementation of these laws led to rioting, and in wake of the violence, the 1984 Police and Criminal Evidence Act introduced new rules for stop and search.

However, equality advocacy groups complained that the law remained vague and open to abuse, and there was evidence of disparities in its use, such as unrecorded and temporary stops of vehicles driven by black or Asian people. Section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 allowed a police officer to stop and search a person without suspicion.

Macpherson and beyond

The 1999 Macpherson report into the murder of teenager Stephen Lawrence proved a watershed in policing, with its conclusion that the Metropolitan Police had been blighted by institutional racism. The immediate effect was a decline in the use of stop and search. In London, stop and searches fell from 180,000 in 1999/00 to 169,000 the following year. Nationally, the number fell by 21% and then a further 16% from 1998 to 2000.

However, this was far from the end of the controversial laws. There were 106 uses of section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act in the year to March 2018, for example, compared with 23 in the same period a year earlier. Section 60 allows officers to stop and search any person without suspicion within an area designated by a senior police officer if they believe violence has occurred, or is about to occur. For every use of section 60, several people could be searched.

The legislation was even criticised by Theresa May in 2014—when she was home secretary—for damaging community relations. Statistics continue to show that stop-and-search powers are disproportionately used against black and minority ethnic people.

As well as tribunal information and police statistics, people’s attitudes are another barometer by which to measure the effectiveness of race-relations legislation. A report published this year by the British Future think tank—called Many Rivers Crossed—has examined the legacy of Enoch Powell’s speech, and the challenges that remain. It highlights a strong generational divide over Powell’s impact.

For younger British people, for example, Powell is almost an irrelevance. According to British Future’s polling, less than a fifth of under-34s (18%) can pick his name from a list when asked who is associated with the phrase “rivers of blood”, compared with 82% of those aged over 65.

A majority (59%) think race relations have improved, saying that there was more prejudice in 1968. However, a third of black and minority ethnic (BAME) respondents said they had experienced racism in the street. Only 17% of BAME respondents had experienced prejudice online, but the figure rose to 27% among 18-24-year-olds.

In the report, senior politicians also have their say, revealing the impact of Powell’s speech on them. “I came to the UK from working in east Africa that year with my wife Olympia, who was east African Asian,” Vince Cable, the Liberal Democrat leader, explains. “There was an ugly climate of racism and rejection that lingered for years afterwards. Gradually, I sensed, race relations improved—at least in the more cosmopolitan big cities.

“Until two years ago I felt positive that the legacy of Enoch Powell’s poisonous and pessimistic rhetoric had been buried. Now I’m not so sure. The ‘immigration panic’—albeit mainly directed at white east Europeans—and Brexit have now brought some dangerous xenophobia back to the surface.”

Asked what he would say to Powell now, Sajid Javid, the Conservative’s communities secretary, replied: “Your old seat is now represented by Eleanor Smith MP, a former nurse and a woman of African Caribbean heritage who is as British as you or, indeed, me. “I’m certain the irony won’t be lost on you. Over the past 50 years, our country has undoubtedly become fairer, and despite setbacks BAME communities are among the highest-achieving in our schools, public life and the private sector. So we have made real progress. But not nearly enough. While BAME employment rates are at a record high, less than 3.5% of people occupying the three most senior positions in FTSE 100 companies are from ethnic minorities. We have much more to do.”

British Future’s research suggests that, while race relations in Britain may have evolved since the 1960s—helped along by legislation— some serious issues remain. For example, there’s a strong expectation among younger voters that there’s further to go in dealing with racial prejudice. There’s also concern that Britain’s Muslim citizens are the ones now facing the most prejudice: most people (56%) said the group face “a lot” of prejudice and a further third (32%) said they face a little. Only 4% said they face no prejudice at all.

Among ethnic minorities, two-thirds (66%) of over-65s and 73% of 55-64s feel that racial prejudice was worse 50 years ago. Among younger people from ethnic minorities, about half think things were worse back then. However, 22% of those aged 18 to 24 think it may have been about the same and 18% think things were better. Then, as now, the picture of race relations is a mixed bag—in spite of legislation.

Academy tools to help you get a job

-

Free Watson Glaser Practice Test

Understand the test format, compare your performance with others, and boost your critical thinking skills.