Legal Spotlight

Law firms are trying to diversify their trainee intakes. But if the institutions from which they’re recruiting are failing to diversify, is there a knock-on effect? We take a look at the diversity problem at the UK’s top universities.

Law is not an historically diverse sector. In 1913, black barristers couldn’t dine alongside white counterparts at Gray’s Inn, while women were unable to qualify as lawyers until 1923. Archaic laws established who would be the minority groups in British law, and who would dominate it. Today, law firms are working hard to reverse this discrimination, to create a more representative workforce—93% of law firms took specific actions to attain diverse intakes in 2017.

But while law firms appear to be moving towards inclusivity, the universities from which they recruit remain exclusive enclaves. In turn, 2014 research revealed that 94% of senior judges were educated at a Russell Group university, with 75% of that same group being Oxbridge graduates. Top universities produce top lawyers—but top universities are brought up time and time again as institutionally and socially lacking in diversity.

“Our elite universities are a conveyor belt into the elite—they set their graduates up for the top jobs in politics, business, law, the media and every other industry,” said Labour MP David Lammy in his speech on diversity in higher education in January this year. “It doesn’t look like our top universities are going to give up their grip on being the route into the best jobs any time soon, so we need to look at who is getting the chance to go to these institutions.”

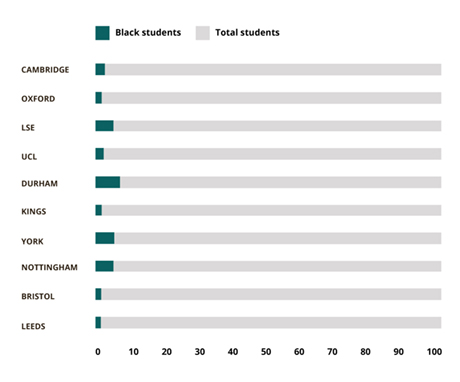

Black British students are chronically underrepresented at top universities. In 2016, just 40 black students were accepted out of the 2,210 placed UK applicants to Cambridge university, while 35 black students out of 2,210 placed UK applicants were accepted at Oxford, a Business Insider investigation found. At Oxford and Cambridge, black students make up 1.7% and 1.5% of the total student population respectively. On a wider scale, 6.9% of the total UK domiciled students are black.

Figures at other high-ranking universities for law show that London universities accept more black students than others within the Russell group—5.7% of UCL’s enrolments in 2016/17 were black students, while at LSE, 5.3% of students enrolled were black. Top universities outside of London fell significantly below the national figures in terms of how many black students they enrolled: at the University of York, just 2.4% of those enrolled were black students, and at Durham the figure was 1.7%. Such figures raise the question: are universities doing enough to attract BME applicants?

Top universities for LLB law (excluding Scottish universities) - % of black students.

"In my first year, the university was looking for people who had gone to certain schools to be Durham university ambassadors at their former schools,” says Tommy, president of the Durham Law Society. “It was immediately apparent that the list was full of grammar schools in the home counties. Just one school on the list was in inner-city London—the place with the highest black and minority ethnic population.”

Student ambassadors are a way for potential applicants to see that they would fit in at a top university, and hear about the experience from someone who’s done it before. “It’s the perfect opportunity to get a broad range of students from a wide variety of backgrounds,” says Tommy. “It seems as though they’re just focusing on the socio-economic stigma of Durham—the public-school-boy type of stigma—and in doing that, they are forgetting about racial diversity.”

Racist incidents

For BME students, getting into university is just the first tentative step. The other part—the one for which students are usually the most isolated—is reaching graduation. Black students are 1.5 times more likely to drop out of university than their peers; one in ten will do so before finishing their degree.

Everyone has different reasons for not completing a degree; but for some, racism can be a major factor in their university experience.

Just last year, Exeter University student and member of the Bracton Law Society, Arsalan Motavali, went public on social media with screenshotted messages of racist and homophobic comments made by his fellow students. The messages had been posted on a group chat comprising some Bracton Law Society members—including Motavali, who left the chat when it “just got too much”. The students who made the remarks were suspended from the university and the law society, and one student lost his training contract place.

At Nottingham Trent University, Rufaro Chisango heard individuals chanting racial slurs outside her room in university halls. Like Motavali, she took to social media, posting “Words cannot describe how sad this makes me feel, in 2018 people think this is still acceptable.” Two students were suspended from NTU in relation to the incident, while one was convicted and had to pay a £800 fine.

In both cases, the students at fault were penalised, but the fact the incidents happened at all are symptomatic of a wider problem at top UK universities: serious racist offences are still carried out by some students, who are under the impression that this is just banter. Other BME students have to contend with racism off-campus, from those local to the university town.

“I’ve been running along the street in the evening and someone has wound down their window and shouted ‘Slave!’,” says Dominic*, a law student at Durham. “There were 15 people around me on the street and none of them even turned around to say anything. It’s almost like by not reacting, people are consenting to this behaviour.”

Part of the problem is the racism itself, but the other part is the way in which universities respond to it—a way that many BME students find inadequate. Dominic describes an incident at a college party: white students were singing ‘Gold Digger’ by Kanye West at a karaoke event. “Obviously the song has the N word in it: not only did they not censor the word, but they proceeded to sing along to it, and adding it in at other points where it doesn’t originally appear.

“When this was reported to the university, they came to the conclusion that it was uncontrollable activity at a college bop [a type of social at Durham colleges]. It basically just exonerated anyone involved. Creating an environment where hostility and intolerance is tolerated is going to make people feel unsafe.” In notable cases of racism at top universities, students often feel discouraged from speaking to the university. Speaking to Newsnight about the Bracton Law Society group chat, Motavali said, “We talked about going through [Exeter] university, but one of my friends had had a far worse situation and it was a five-month investigation and an outcome that was incredibly vague.”

Meanwhile, Chisango described how she reported the racist chanting outside the door to her halls, as well as writing a statement and sending it to the university, but heard nothing back—only after she posted on social media did she get a response.

“There have been several instances of things that have happened at university, and the only thing that the university can say is that ‘we have a zero-tolerance policy’,” says Tommy. “But what does that mean? What are the repercussions of that, of harassing someone for the colour of their skin or for where they come from? There’s no point in saying that there’s a zero-tolerance policy if you’re not going to do anything about it.”

Pursuit of real change

People of Colour organisations and African Caribbean societies offer a positive environment in which to celebrate shared culture, as well as a base from which to rail against on-campus racism. While the presence of these groups is vital, it isn’t their responsibility to ensure their members are safe on campus—the university must ensure it’s putting its diversity and inclusion policies into practice.

David Lammy says that universities need to get “serious about contextual data”—an aspect of recruitment to which many law firms are already paying attention. “The issue that they have to address is that a student living on the 20th floor of Grenfell Tower with an unstable home life, caring responsibilities and nowhere to do their homework is expected to jump through the exact same hoops as a privileged student at Eton or Harrow.

Surely the top free-school-meal student at an under-performing state school is more talented than an average student at a public school, and all the evidence backs this up.” To do this means to “fundamentally rethink how we define merit and ability”.

Yet in order for universities to succeed at being racially diverse, racist incidents within these institutions need to be dealt with; there’s no point in pushing a student to achieve a place at a top university if they won’t feel safe and accepted enough to stay there. “Diversity is more than just numbers,” says Tommy. “It means creating a tolerant atmosphere.”

Reflecting on his own experiences at Durham and those of his peers, Dominic says that policies on racial harassment need to be clearer. “When things do happen, they need to be taken seriously, with steps being taken to remove the harassers from university. If you fall out of line within a tolerant environment you should be removed from that environment.

“Obviously it’s a minority of people, but it’s a toxic minority—and that just poisons the whole atmosphere. It makes you forget about the 200 days you’ve been at uni where nothing’s happened, because of the one day that something did happen and nothing was solved.”

Commenting on the incidents, Durham University’s deputy vice-chancellor and provost, professor Antony Long, said that college bop was “fully investigated by the college concerned and appropriate actions were taken, which resulted in the complainant thanking the college for its response.”

Long went on to say that student ambassadors were assessed “on the basis of their ability, not their background”, and that the university “welcomed students from all backgrounds with merit and potential”. He added that the university has committed £11.5 million to outreach-related activities for 2018-9, and that it “does not accept any form of prejudice or discrimination”.

*Some names have been changed to protect individuals.

Academy tools to help you get a job

-

Free Watson Glaser Practice Test

Understand the test format, compare your performance with others, and boost your critical thinking skills.