Legal Spotlight

Alongside traditional courtroom cases, many public figures who get into legal trouble find themselves facing the court of public opinion. What are the implications for the course of justice?

Juries and judges that go against the general consensus are nothing new. Perhaps even more common is the perception that official legal proceedings are too slow, discriminatory and not harsh enough.

Enter the court of public opinion: a phenomenon with both positive and negative implications, existing separately from—but unmistakably fuelled by—decisions made by judicial systems. In high-profile cases, usually those of celebrities, intense media scrutiny can lead to a whole new system of trial and punishment, exacerbated by the importance placed on online reputation. Through hashtags and article shares, public opinion acquires unprecedented power over individuals facing legal strife. This emotional response can be a blessing or a curse; a worthy prosecutor or a misguided one.

Case study: the Ulster rugby rape trials

One case in which public opinion would eventually become vital— described as “too big and burly for the confines of a courtroom” by the BBC—is the Ulster rugby rape trials. Paddy Jackson and Stuart Olding, together with Blane McIlroy and Rory Harrison, stood trial for nine weeks, accused of raping a 19-year-old woman. They were found not guilty.

Social-media users reacted in horror to the verdict. Screenshots of panicked messages sent by the young woman the morning after the alleged rape were scrutinised by Twitter users, alongside self-congratulatory messages sent by the four men the same morning. The public became even more incensed when it emerged that the alleged rape victim spent eight hours on the stand, had her underwear examined in court and her sexual history questioned. The accused, on the other hand, spent just two hours each under scrutiny.

It is difficult to separate emotion from a rape trial, particularly one in the aftermath of the #MeToo movement and featuring a young woman who had apparently taken all the “right” steps after a rape: seeking medical attention and, later, reporting it to the police. The presence of two well-known rugby players also meant it was possible for commentators to go down the “lad culture” route, or focus on the closing down of rape-crisis centres.

But amid all the think-pieces, the root of public outrage was the facts. The screenshots were scrutinised, unbiased court reports were dissected on Twitter, and the conduct of the barristers involved in the trial was called into question. Rather than within the courtroom, this was all happening online.

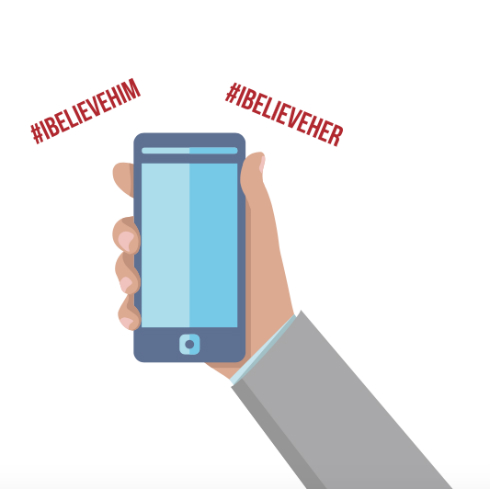

The hashtag #IBelieveHer, in support of the woman, emerged after the men were acquitted in late March. The message was clear: if the men weren’t shamed in a court of law, they would be shamed online. People from all over the world competed against each other, under #IBelieveHer and—in support of the men— #IBelieveHim. The court of public opinion began a fresh trial after the legal one had ended.

During the actual trial, public commentary and social media were closely monitored by the prosecution and defence alike, in order to identify anything that could sway the jury. But while the jury wasn’t swayed, Ulster Rugby was. As a result of the reputational damage caused by the social-media storm, the men were sacked from the club and told they wouldn’t play for the Irish national side.

Ads in the Belfast Telegraph , paid for by supporters of the men, stated that the clubs “should not bow to the court of social media”, while an ad from supporters of the women “demanded” that “neither of these men represents Ulster or Ireland now or at any point in the future”.

Rape is seldom reported, and seldom results in a guilty verdict when it is. The victim herself said in one of her widely-circulated messages, “I’m not going up against Ulster Rugby. Yeah because that’ll work.” The Ulster rugby trial is one in which certain members of the public examined the facts, as well as the situation in court, and decided that an error had been made. They sought to hand down a different sentence, one which stripped the men of their positions on the rugby team.

Case study: R Kelly

The consequences of widespread outrage against celebrities— financial loss, career restrictions and loss of platform, to name a few—can be seen as compensation for a fair trial and verdict. And while for victims’ peace of mind some retribution is better than none at all, the actions in response to online scrutiny cannot be a substitute for justice.

Earlier this year, R Kelly became the first artist whose music will be removed from Spotify-owned content and playlists due to “hateful content and conduct”. This isn’t a judgement on R Kelly’s music; rather, it’s due to the allegations of sexual abuse made against him over many years.

Spotify’s regulations state: “Hate content is content that expressly and principally promotes, advocates or incites hatred or violence against a group or individual based on characteristics, including, race, religion, gender identity, sex, ethnicity, nationality, sexual orientation, veteran status or disability. We do not permit hate content on Spotify.”

While Spotify’s decision comes as welcome news for some, others have pointed out that the rapper hasn’t yet been convicted of a crime—Spotify came to its decision before a court of law did.

It’s also difficult to understand why Spotify has applied this policy to a couple of artists while ignoring others. The management of XXXTentacion—the recently-murdered rapper whose content was removed on the same grounds—released a statement asking if other artists who had been accused (but not convicted) of violent, sexual or hate-inciting crimes would also have their work removed.

It seems fair that the activists highlighting these crimes should be able to choose their cases—a sentiment shared by #MeToo founder Tarana Burke, who commented, “This is the battle I’ve picked. There’s always going to be somebody else.” She explained that she chose to speak out against R Kelly because he used “every dime” earned from his music to “brutalize black and brown children”.

Spotify, on the other hand, doesn’t have the personal passion of an activist, and the picking of a battle by a corporation can feel like a PR stunt.

Corporations as judges?

Justice systems make a point of punishing crimes proportionately. When a person who told a lie or used a racist slur is attacked with the same venom as a murderer or rapist, the sway held by public opinion becomes difficult to rely on.

Yet weight is still given to the court of public opinion. Spotify and Netflix have reshaped themselves into judges, handing down sentences to disgraced artists in the form of cancelled shows and removed music before their actual trials have been established. Trending hashtags have become the jurors’ verdicts of the modern day.

This has given rise to many successes, but online outrage cannot be seen as a substitute for criminal proceedings. The length and weight that goes into a trial cannot be substituted by those on Facebook and Twitter, where users pick and choose what they see anyway.

Other cases—such as the recent visit of Kim Kardashian to the White House to discuss prison reform—result in an element of chance being introduced to justice. Kardashian’s visit resulted in a pardon for Alice Johnson, a woman whom Kardashian cited as an example of an unfair drug conviction. Johnson was lucky to be on the right side of Kardashian’s agenda, but thousands like her will remain incarcerated—there has been little movement to reform the system that imprisoned Johnson in the first place.

“Public opinion most strikingly influences the law in much the same way—through pressure,” wrote Sanel Susak in the Nottingham Law Journal . “It exists as a background presence and, because the public is not a maker of law, can only influence decisions and actions.”

And perhaps this is where public opinion should stay—giving voice to instances where the conventional justice system has got it wrong, speaking up for the marginalised and putting pressure on the relevant people to bring about reform. A trending hashtag can never equate to a guilty verdict, but it does have the power to lull society into a false sense of justice.

Academy tools to help you get a job

-

Free Watson Glaser Practice Test

Understand the test format, compare your performance with others, and boost your critical thinking skills.