Commercial Insights

As the US edges towards a trade war with other countries, concern about the future of trade between the UK and the EU is also on the rise. So how will this legal minefield be negotiated?

US President Donald Trump has been on a months-long tariff spree, kicking off potential trade wars with several countries by sticking tariffs on everything from steel to chicken incubators, and declaring on Twitter in March: “When a country (USA) is losing many billions of dollars on trade with virtually every country it does business with, trade wars are good, and easy to win.” Trading partners of the US—including China, Canada, the EU, and Mexico— have since hit back with retaliatory tariffs.

Trump has history with his ‘dog-eat-dog’ views on trade. In the 1980s, the real-estate mogul railed against the US's trade deficit and warned of “other countries ripping off the United States”. In a 1990 Playboy interview, Trump was asked about his first action if he ever became president. “Many things. A toughness of attitude would prevail,” he said. “I’d throw a tax on every Mercedes-Benz rolling into this country and on all Japanese products, and we’d have wonderful allies again.”

So far, Trump has used tariffs as the main weapon in this trade war; a tax on a good coming into the US, also known as a duty. These duties are collected by the Customs and Border Protection at the good’s port of entry. Once tariffs go into place, importers face the extra fee immediately.

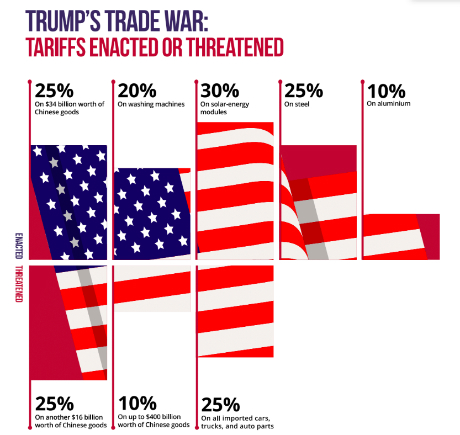

Trump’s hard line on trade kicked off in February this year, when the administration officially placed tariffs on imports of washing machines and solar-energy equipment. In March, he then announced a 25% tariff on imported steel and 10% tariff on imported aluminium. This move triggered widespread pushback from allies, since the tariffs were apparently implemented on ‘national security’ grounds.

Allies such as Canada, the EU and Mexico argue that they pose no national-security risk to the US and thus should not be slapped with tariffs. Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau said in an interview with NBC in June: “One of the things that I have to admit I’m having a lot of trouble getting around is the idea that this entire thing is coming about because the president and the administration have decided that Canada and Canadian steel and aluminium is a national-security threat to the United States.

“Our soldiers have fought and died together on the beaches of World War Two and the mountains of Afghanistan and have stood shoulder to shoulder in some of the most difficult places in the world.”

Tensions are running high on this side of the Atlantic too. Leaving the EU without a trade deal could leave British households almost £1,000 worse off a year, according to a recent report, meaning pressure is on the UK to strike one. If Britain left the bloc and reverted back to World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules, there would be import tariffs and the UK would leave the EU Customs Union and the Single Market. As a result, each household would probably be £960 worse off, the report by multi-national consulting firm Oliver Wyman has suggested.

Talks are still ongoing at the time of going to press, but the UK could refuse to pay its divorce bill to Brussels if it does not get a trade deal, the Brexit Secretary has warned. Dominic Raab—who replaced David Davis after he quit the role in July— said “some conditionality between the two” was needed.

Raab said that the Article 50 mechanism used to trigger Britain's exit from the EU provided for new deal details. He told the Sunday Telegraph: “Article 50 requires, as we negotiate the withdrawal agreement, that there’s a future framework for our new relationship going forward, so the two are linked. “You can’t have one side fulfilling its side of the bargain and the other side not, or going slow, or failing to commit on its side. So, I think we do need to make sure that there’s some conditionality between the two. “Certainly it needs to go into the arrangements we have at international level with our EU partners. We need to make it clear that the two are linked.”

During the ‘transition’ period — from March 29, 2019 to December 31, 2020 — free movement will continue, as the EU wanted, but the UK will be able to strike its own trade deals (although they won’t be able to come into force until January 1, 2021). The UK will need this time. It will be excluded from EU arrangements with ‘third countries’ (trading partners outside the EU), entering the equivalent of a legal void in key parts of its external commercial relations. It will then have to start 750 separate time-pressured mini-negotiations worldwide, according to Financial Times research.

Through analysis of the EU treaty database, the Financial Times found 759 separate EU bilateral agreements with potential significance to the UK, covering trade in everything from nuclear goods, customs and fisheries, to trade, transport and regulatory co-operation in areas such as antitrust (competition law) or financial services.

This includes multilateral agreements based on consensus, where the UK must re-approach 132 separate parties, according to the Financial Times’ research. Around 110 separate opt-in accords at the UN and World Trade Organisation are excluded from the estimates, as are narrow agreements on the environment, health, research and science. Some additional UK bilateral deals—outside the EU framework—may also need to be revised because they make reference to EU law.

Some of the 759 separate EU bilateral agreements are so essential that it’s almost unthinkable for the UK to operate without them. Air-services agreements allow British aeroplanes to land in the US, Canada or Israel, for example, while nuclear accords permit the trade in spare parts and fuel for Britain’s power stations. Both these sectors are excluded from trade negotiations and must therefore be addressed separately. With Switzerland alone there are 49 accords, while there are 44 with the US and 38 with Norway. As international trade becomes more complex, so too do the legal frameworks within which they operate.

Academy tools to help you get a job

-

Free Watson Glaser Practice Test

Understand the test format, compare your performance with others, and boost your critical thinking skills.